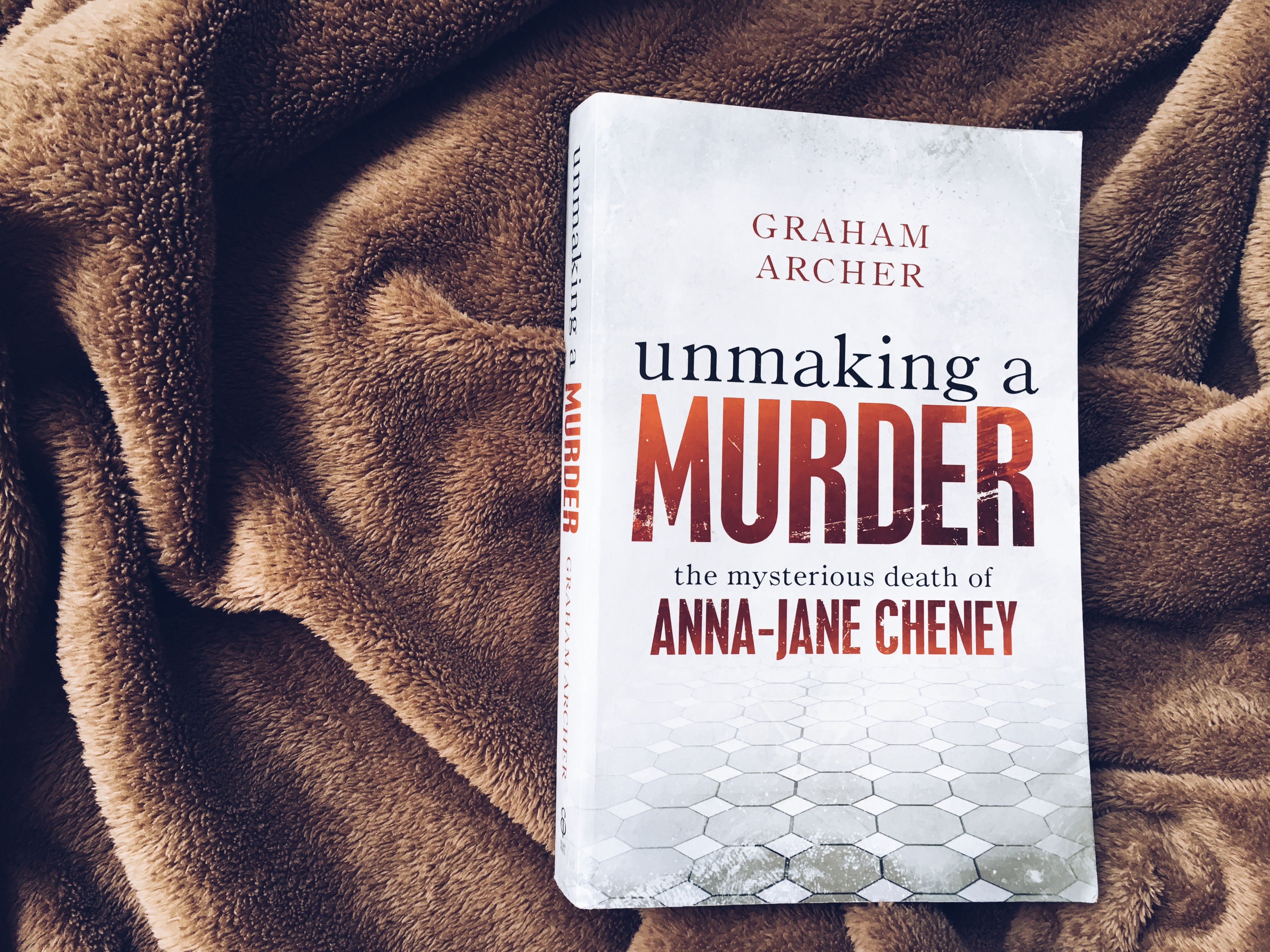

If you think Making a Murderer was a shocking story of sub-par investigating, potential cover-ups and conspiracies, and a total indifference towards truth and justice, then Unmaking a Murder should be your next read.

I read this true crime book a couple of months ago – thanks Dad for letting me borrow it and take it across the world – and I’ve been reeling ever since. It was a familiar case to me, as it would be for most people from Adelaide, who would have heard of Henry Keogh and followed the media coverage of his case over the years.

So I opened the book thinking I knew – in rough details, at least – what had happened. But I couldn’t have been more wrong.

The story of Henry Keogh’s unfair trial, and the political power play that ensued for 20 years, is utterly unbelievable. I try not to be a cynical person, but it makes you question a lot when you realise that someone’s life has been used as a kind of political pawn, with truth being nothing more than an inconvenient detail to be worked around.

The mysterious death of Anna-Jane Cheney

In 1994, Anna-Jane Cheney was 29 years old. She was working at the Law Society of South Australia, she was popular and well-liked, and she was engaged to be married to Henry Keogh, who was 39 years old at the time. One evening in the March of that year, Henry arrived at the home the couple shared after visiting his mum to find Anna-Jane lifeless and submerged in the bathtub.

When police arrived, they failed to secure the home as a crime scene, as Anna-Jane’s death was initially treated as unsuspicious. Photos weren’t taken, evidence was contaminated and, crucially, Anna-Jane’s body was moved and handled.

Just days later, suspicions of murder began to bubble up, and Henry quickly became the South Australian police’s main suspect. The police believed they had plenty of evidence. There were fake life insurance policies that meant Keogh would receive a sizeable payout in the event of Anna-Jane’s death. There were alleged affairs, family tensions…and then there were the bruises on Anna-Jane’s ankle.

During trial, the state’s chief forensic pathologist, Colin Manock, theorised that the bruises he claimed to have seen were caused by Henry gripping Anna-Jane’s ankles to lift them over her head, thereby drowning her. This was one of the key pieces of evidence presented by the prosecution at trial, and much of their case against Keogh hinged on Manock’s drowning theory.

After a hung jury in March 1995, Keogh was found guilty at his second trial in August of the same year, and sentenced to 25 years without parole in Yatala Labour Prison. Keogh never wavered in his claim of innocence, and began looking into appeal options immediately.

There was an incredible amount of media interest throughout the trials, most of which was shamelessly one-sided, and by the time Keogh was convicted, many people saw him as a cold, calculating killer, completely deserving of his sentence. The news of his plans to appeal were met with disgust.

What they didn’t know was that the pathologist, Colin Manock, was completely unqualified for his job, had made terrible, devastating mistakes in the past, and that the supposed ‘evidence’ of bruising actually didn’t exist. In addition, the method of drowning, which he presented at trial, was later found to be at the very least unfeasible, if not impossible. There was no proof that Anna-Jane’s death was anything more than a tragic accident.

Let me say that again: Henry Keogh was convicted of a murder that probably never happened.

Despite this, Keogh remained behind bars for an unthinkable 20 years.

Unmaking a Murder

Henry Keogh. Image source: theaustralian.com.au

What happened next – the fight for Keogh’s right to a fair trial, and the complete refusal of the system (I hate using that term as it makes me sound like a tinfoil hat-wearing conspiracy theorist, but in this case there really isn’t a better description) to acknowledge their mistakes – is what journalist Graham Archer covers in Unmaking a Murder.

The author was uniquely placed to write this story, and the details he’s able to offer make this book so much more than an average true crime account. Graham Archer is one of Australia’s leading investigative journalists, and was working for one of the country’s biggest broadcasters at the time. Because of his position, he had access to many of the major players, on both sides of the struggle for Keogh’s freedom.

Archer manages to clearly explain the political intricacies, which were central to the case, in a way that contextualises what otherwise would look like a baffling and unconnected series of events.

Having said that, I have to admit that I didn’t always enjoy Archer’s style of writing. Perhaps it’s inevitable for someone close to the case, but he has a tendency throughout his telling of Keogh’s story to make it about himself, rather than the case. At times, he uses the book as a platform from which to share how right he was about something, or how he was wronged by those around him. That’s not to say he wasn’t wronged…it just felt a bit unnecessary to the story.

So his style did grate on me a bit at points throughout the book. But despite that – or maybe it was exactly because of Archer’s keen sense of justice – he fought tirelessly to turn the public tide of opinion and to make sure Henry Keogh eventually received justice.

He didn’t do it alone, but he was one of the few who believed in Henry Keogh when countless others were ready to dismiss him and believe what the Government, the criminal justice system, and almost all of the other media outlets were saying. And to be perfectly honest, if I were in a situation like Keogh’s, it’s someone like Archer I’d want fighting in my corner. His contribution to the outcome of the case was incredibly significant.

The Conclusion

It’s no spoiler (it’s on the jacket of the book, and a quick Google search would tell you anyway) to reveal that Keogh was eventually released – after 20 years behind bars – when the laws around appeals were changed.

Even then, knowing that there was no evidence to support Anna-Jane’s death being a murder, and knowing that their chief forensic pathologist was unqualified and prone to making huge errors – the Director of Public Prosecutions fought to keep Keogh behind bars.

Unmaking a Murder is a shocking look at the lengths the system (the government, the justice system, the elite) will go to in order to protect themselves, and the effects on those who are left in their wake.

I’m so glad I read this book (although it was an uncomfortable read); I think it might be one of the most shocking true crime stories I’ve ever come across. Oh, and in case you’re wondering what Henry’s up to these days, he’s still fighting for the full truth of his case to be revealed. I really hope those who knowingly kept an innocent man behind bars get the justice they denied him in the end.

On that note, I’m off to watch When They See Us, because apparently I can’t resist being outraged. But really…when will our systems stop doing this to people?! It’s madness.

Have you heard of Henry Keogh’s case before? Or are there any other barely-believable cases you’ve heard of that I should know about? Let me know in the comments below.